By the time I became a parent, I had definite ideas about how I wanted to raise my child. One thing was certain: I wanted her to know more than one language. As a former bilingual education teacher who has taught at the public school and university levels and traveled extensively overseas, I knew the value of having more than one language. And as the parent of a child born in a Spanish-speaking country, I felt that knowing Spanish would give my daughter an important connection to her birth culture.

At first, raising Marisa to be bilingual was easy. Since she’d spent her first six-and-a-half months in Guatemala, she was used to Spanish, and it was apparent that she preferred it. On the street, she turned toward people who spoke Spanish, and she liked it better when I read to her in Spanish. I sang Spanish songs to her, and we watched “Plaza Sesamo” (“Sesame Street”) on Spanish TV. My efforts paid off. Marisa’s first words, after “Mama,” “uh oh,” and “dipsy,” were Spanish words—”leche” (milk), “agua” (water), “más” (more), and “mano” (hand). She even taught her day care teacher to say them.

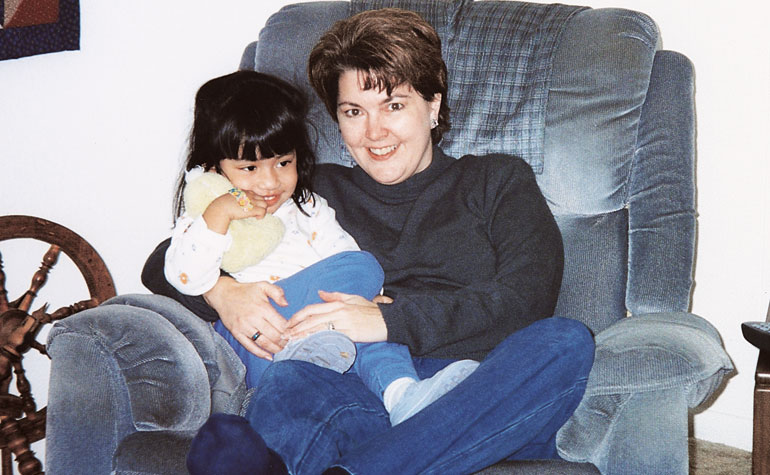

Now that Marisa is three, raising her to be bilingual is more of a challenge. She spends a good portion of her day in an English-speaking day care program. Many of her friends speak only English, as do her grandparents, who moved to be near us two years ago. Marisa now shows a definite preference for English. But I remain determined to help her develop Spanish proficiency. Below are some of the approaches I’ve discovered over many years of teaching—and a few very instructive years of parenting.

Know Your Goal

It’s important to begin with a clear idea of what bilingualism means to you. Some people consider it to mean understanding both a first language and a second language. To others, bilingualism means being able to speak, understand, read, and write two languages. Still others say they want their children to be bilingual but actually mean they want them to be exposed to their birth language so that it will be easier to study when they are older. Knowing your own definition will help you set goals for your children.

Be Realistic

In a family in which no one speaks a language other than English, it will be difficult, though not impossible, to raise a child to speak, understand, read, and write two languages with absolute proficiency. Think about how a child acquires his first language. When learning to talk, he receives a lot of support. Family members talk to the child and respond positively to his speech. The child hears the same language on TV, in bedtime stories, and at school. This goes on for 12 to 14 hours a day. The child isn’t aware of acquiring language—it begins before he speaks. All the time the child spends hearing the first language is part of the acquisition process.

A few hours of vocabulary activities a week won’t lead a child to become fluent in a second language—or to maintain a first language while acquiring a second language. Parents who want their child to be bilingual have to understand that he needs equal exposure to both languages. Learning is easier if one or both parents speak two languages.

Consider Your Child’s Age

Of course, a child who is adopted from another culture at an older age will already have acquired a language other than English. While he may have some delays in his first language due to having lived in an orphanage or not having had much interaction with adult speakers, he will already possess quite a bit of verbal ability. A bilingual education program can be beneficial for maintaining proficiency with the first language as he acquires English. The child is taught new concepts and skills in the language he understands, while he concurrently develops proficiency in English. Though some parents fear that continued education in a first language will impede the acquisition of English, the opposite is actually true. The stronger a child is in his first language, the better developed his second language becomes.

For a younger adopted child, the parent is faced with fostering two languages simultaneously. This can be done, but it takes effort.

Decide on an Approach

Many families use a method called “one person, one language,” in which one parent speaks to the child exclusively in one language, while the second parent uses the other. If the parents speak only one language, a nanny or au pair who speaks another is an option. In my situation, I am Marisa’s Spanish model, and her grandparents and preschool teachers are her English models. It’s as if she’s acquiring two first languages.

Another option is the “one place, one language” approach, in which the language the parents speak is used in the home, and another language is used outside of the home. To do this, parents need to find a day care or school in which the caregivers/teachers speak the other language. Immigrant communities sometimes have centers in which their native language is spoken, or home-based day cares in which the caregivers speak exclusively or primarily their native language. The local school district can be a good source of information on the availability of these options. The most important thing is to decide on an approach and to stick to it.

Investigate Educational Options

Some schools offer foreign language education (FLE) programs. These provide a lesson in a foreign language to students, either daily or weekly. This brief exposure won’t be enough to develop proficiency in the non-English language, but it will support other language learning efforts.

Some places offer immersion programs. In these, children are taught entirely in another language. Teachers use special techniques to make instruction comprehensible. One version of this approach is called dual language (also referred to as two-way or bilingual) enrichment. In this program, students from two language backgrounds are placed together in one class, and the teacher alternates languages for instruction. In some dual language programs, the teacher teaches in one language one day, the other language the next. In other programs, some subjects are taught in one language, others in a second language. A directory of dual language programs can be found on the Web site for the Center for Applied Linguistics.

Saturday language schools are also available—most frequently, in areas with Chinese- and Vietnamese-speaking populations, usually provided by community organizations. An extra benefit of enrolling an adopted child in a Saturday program is that the parents can also meet adult speakers of the second language.

Finally, language study in another country can be good for the whole family. Study-abroad programs often involve staying with a host family who speaks only the language being learned. Classes tend to be small and taught entirely in the non-English language. Many programs also offer dance, music, and cooking classes—all wonderful opportunities to learn about a culture.

Locate Resources

Often parents can find religious services in the non-English language. Immigrant organizations and play groups are also helpful. Exchange student organizations are another resource. Even if your family is not able to host an exchange student for a year, there are short term exchanges and weekend events. These provide opportunities for the adoptive family to interact with other speakers of the non-English language and to learn about other cultures as well. Communities with large immigrant populations sometimes offer library story hours in non-English languages.

Books, magazines, story books with cassettes, videos, music, and computer programs can all support language development. Public libraries often offer these resources. Marisa’s favorite video is El Rey León (The Lion King), which we check out at least once a month. She also loves her CD’s in Spanish and asks me to play them in the car.

Watching quality programming in another language (where available) can support language acquisition. “Plaza Sesamo” (“Sesame Street”) is available on Spanish television channels in many areas of the United States.

Keep in Mind…

Children who are raised bilingually from birth (or close to birth) often begin to speak later. This may be because they need time to sort through the two languages and make sense of what they are hearing. But they quickly reach age-appropriate language levels. You may find it necessary to explain this to other family members.

Children who learn two languages sometimes mix them; this is a normal stage in the development of bilingualism. As they become more proficient in each language, the mixing will taper off.

Raising children to be bilingual takes time and dedication. But the benefits, especially for children adopted internationally, make it all worthwhile.