A few weeks after my daughter’s sixteenth birthday, I proposed a trip to her: Would she like to go back to the town in China where she was found and get to know girls her age who grew up there? She’d been abandoned in Xiaxi Town, a farming community of some 40,000 residents, when she was three days old. I adopted her as a single mother at nine months old. I sensed that meeting “hometown” girls might help her to find some valuable missing pieces of her Chinese identity.

For some adoptees, the desire to connect with their birth family exerts a powerful tug. Maya had expressed no interest in searching for her biological roots, but it turned out that returning to Xiaxi in this way interested her, and this thrilled me. For nearly a decade, I’d believed I owed my daughter this kind of an opportunity as a way of making up for what I felt was my worst day of being her mother.

Maya and Jennie, then known as Chang Yulu (Maya, front left crib) and Chang Yuchang (Jennie, second left crib) in the Social Welfare Institute in Changzhou. This photo was taken the day before they left the orphanage with their new moms in June 1997.

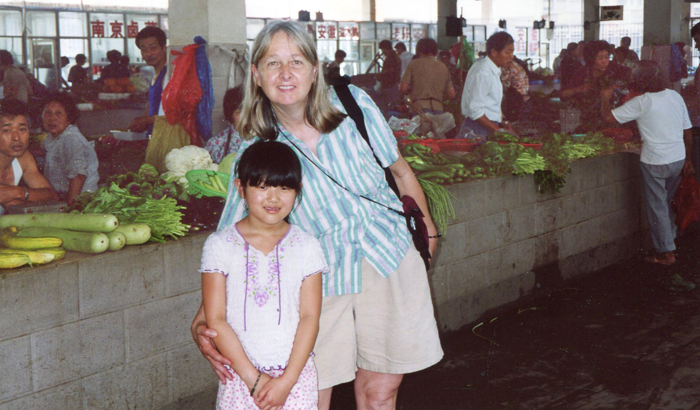

On that day in June of 2004, I’d taken Maya to Xiaxi. She was seven years old. She and I were at the tail end of an exhausting three-week journey in China, our first time back to her birth country since her adoption. Maya had said she wanted to go back to her orphanage, so before flying home we’d traveled by train from Shanghai to Changzhou. At the orphanage, she walked among the many rows of cribs, and then held one of the babies. The director hosted a luncheon banquet in honor of Maya and another adoptee who was also visiting that day. Her visit there went so well that, impulsively, I told her we’d go Xiaxi the next morning; it wasn’t far away, about 25 kilometers. Why not see this place where she was found, even though her adoption papers hadn’t given us the exact location?

That morning our driver parked the car on the town’s main street. When we walked into the bustling outdoor market, merchants and customers turned to stare at us. We made an odd pair, especially in a rural town where nobody saw anybody with blonde hair and white skin, except on TV. Maya held my hand. Her expression could be read without translation; it said, “I’m scared.” Likely, many wondered if I’d kidnapped this child. A few women approached Maya and tried speaking with her. She couldn’t understand, nor did she reply with the words, Ni hao, “hello” in Mandarin, as she’d politely done during the rest of our trip. Instead, she froze and stayed silent.

Maya tightened her grip on my hand and I knew we had to leave. From the car’s back seat, I asked the driver to take us to our hotel in Changzhou. The rest of the day Maya watched TV in our room without saying a word. Meanwhile, I scolded myself for being so poorly attuned to my daughter’s feelings. I’d neither prepared Maya for what we’d encountered, nor had I paused to think about whether she was ready to absorb the range of emotions that such an experience would stir in her. I felt awful. I apologized.

I also made a promise to myself: Someday I’d help my daughter to go back to Xiaxi in such a way that she would not feel like such an outsider. In August 2013, with Maya about to start her senior year of high school, that promise was fulfilled. As a bonus, her friend Jennie, who had lived in a neighboring crib in their orphanage, asked to come along when Maya described the journey. Jennie wanted to explore her rural town, Xixiashu, in this same way. As Maya and Jennie spent time with “hometown” Chinese girls, the two American adoptees were able to lean on each other.

This time, I stayed behind in Changzhou with Jennie’s mother while our daughters went to their rural towns. This was their journey to make, not ours.

I’m now using my lifelong experience as a journalist to produce a digital storytelling experience about these American and Chinese girls’ cross-cultural discoveries. Our project is called Touching Home in China: in search of missing girlhoods. The stories are published on the Web (touchinghomeinchina.com) and as transmedia iBooks (available via iTunes). We have also begun developing curriculum to accompany each of our six stories/iBooks into classrooms.

In the pieces that follow, Maya and Jennie discuss what the three weeks in their “hometowns” in China meant to them.

Claiming My Own Identity

BY JENNIE YUCHANG LYTEL-STERNBERG

Participating in the interactive book project, Touching Home in China: in search of missing girlhoods, has forced me to confront my feelings about adoption and insecurities that I had thought I had overcome. Exploring the town where I was found, Xixiashu, and meeting girls who lived there gave me a snapshot of what my life might have been like had I not been adopted; now, two years later, I feel as if I am finally ready to tackle the implications of that life-altering journey.

When I was younger, I used to play the “what if” game, in which I would imagine my birth parents and the situations that led to my abandonment. Considering all the possible explanations for why I might have been abandoned yielded a range of results. Could it have been that my parents felt ill equipped to handle a baby and gave me up because they wanted what was best for me? Or was it that my parents gave me up in order to have a son? Since I’m a methodical and analytical person, I believe the latter is the most likely scenario. But instead of providing clarity or closure, it only opens up more questions. Did my parents ever have the son they wanted? Do I have other sisters who were abandoned in my parents’ quest for a precious son?

There is a Hebrew word my mom always used to say—besheret, which means “meant to be.” She would say it to be comforting and sweet and it fit perfectly with the idealized notion that adoption had somehow “rescued” me from a horrible future, but most of the time I found the phrase absolutely intolerable. I refused to accept that my adoption was as black-and-white as people wanted it to be. I didn’t and still don’t understand how the people who gave me life, the people who were supposed to love me unconditionally, decided to give me up, leaving me trapped in a life of uncertainty and unanswered questions about my family history. But that doesn’t mean I was ready to label them as villains.

In Xixiashu, one woman I spoke with told me that her factory job was the only way she could send her son to school. Like many of the women in the village, my birth mother probably would have been a factory worker or a farmer. She would have received meager pay for countless hours of work at a mundane task just to send me to a mediocre school where I would not have had the opportunity to learn how to think critically. In seeing such hardships, I began to respect and appreciate my birth parents for making the difficult decision that allowed me to grow up in an affluent society with limitless possibilities. However, even with the freedom and power that I receive as an American citizen, I still don’t know if it could ever make up for the loss of identity that I experienced.

While I initially went to China with the intention of discovering what my life might have been like, questioning and rediscovering my identity became my primary task upon returning. I grew up in a suburb with limited diversity. Being a Jewish, Chinese immigrant with two Caucasian mothers attracted a plethora of questions and unwanted attention. To fit in with my friends and peers, I began conforming to social norms. As a result, through the years I lost my sense of culture and began to identify more as American than as Chinese.

In high school, however, I made some Chinese friends. The more time I spent with them, the more people saw me as Chinese—and the more I identified myself as such. Mistakenly, I assumed I had found a group of individuals with whom I could identify, and I vividly remember the moment that belief was shattered. I was sitting with a group of friends when one of us noticed we were all of Asian descent. But another friend looked at me and said, “You’re not really Asian, though.” Through the years I have heard all kinds of racist comments about my appearance, my intelligence, and my driving ability, but no comment had ever made me feel so alone or dejected as hers did. Her words made me feel like a fraud. It fueled in me an insane, invasive, and incessant desire to prove myself and show this girl and any other Asian out there that I was just as Asian as any of them.

My Chinese identity was forced upon me by a xenophobic society that refused to accept that I could look different and still be as American as a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant. However, in trying to fit in with my “own kind,” I was similarly rejected due to my “whitewashed” childhood. No matter how hard I tried I couldn’t feel fully Asian, nor could I feel fully American.

Jennie (left of center, wearing a black shirt) with her friend Jin Shan, Shan’s grandmother (between the girls), and others from their village.

While I was in China, people pointed out these differences in me. They’d say that, while I looked Chinese, there was something different about me—in my eyes or in how I carried myself or in the ways I acted—that made me stand out from the local girls. Again I felt like a fraud, but instead of feeling frustrated, I was scared and upset. Are my appearance and my abandonment papers the only things about me authentically Chinese?

My questions parallel the nature versus nurture debate. Was the “essence” of being Chinese contained in the DNA I inherited from my Chinese birth parents? Or has my American upbringing negated my birth heritage and made me just an American girl masquerading in the body of a Chinese girl?

In retrospect, I ask myself why I was so scared of being seen as American when I was younger. I realize now that most of this stemmed from my need to prove that I was Chinese. The way that girl described me as “not really Asian” made it seem as if I were tainting the Asian name with my Americanness. It felt as if I needed to hide and abandon the American aspects of myself to fit in with this exclusive Asian group.

Now, I am beginning to believe that my identity is about who I am as me and I should not be defined by other people and the categories in which they want to place me. If I have learned anything from being a college student on a liberal tilting campus, it is that individuals are in charge of claiming their own identities, and that we don’t have to align ourselves with any socially constructed group.

In these past two years, I have been trying to let myself accept my crazy and confusing cultural mix of Chinese and American identities and come to terms with their dynamic, ever-changing nature. I am learning that my Americanness does not have to detract from my identity as a Chinese person. Nor do I need to hide or forsake any part of myself or my upbringing to fit into anyone else’s notion of what it means to be Chinese, American, or even Chinese-American. Realizing this doesn’t necessarily rid me of my insecurities or leave me feeling entirely content with the ambiguity of what it means to be a Chinese-American adoptee. But I do feel I’ve moved a few steps closer to accepting and being comfortable with the uncertainty.

Permeating Boundaries

BY MAYA XIA LUDTKE

The first nine months of my life are a mystery.

A tiny jade bracelet and a photograph of an impossibly circular face above a torn red sweater make up my memory album. A few stapled pages of ambiguous papers constitute my birth record. I do know that I was found in Xiaxi, a farming town of flowers and trees. Though I was nervous about shattering the stable but fragile image I had created in my mind about those nine months, this past August I went to Xiaxi and began to crack through that tableau and experience what my life could have been.

There, I met girls I could have grown up with, and with them visited places where I might have spent each day. I was overwhelmed by simultaneous feelings of deep connection and unbridgeable distance. As we struggled to narrow the chasms created by language and culture, I found familiarity in their faces and the trees enveloping us.

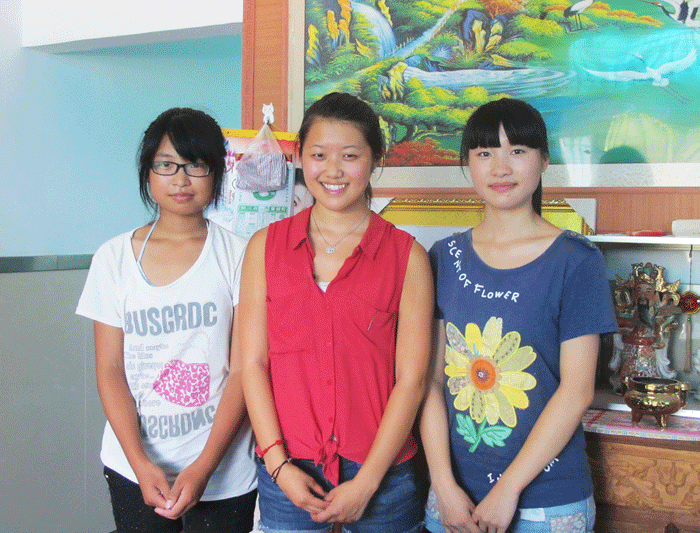

Maya (center) with her Xiaxi friends Chen Chen (left) and Yuan Mengping (right).

“So, what are you?” the girls asked me. “You look Chinese on the outside but you are American on the inside.” At first, I detested this description. If the substance of my being is not Chinese, I might as well be white. Once content with describing myself as “Chinese American,” now I was hit with its vagueness. Where do I belong between being Chinese and becoming American? In some ways my new friends were right; our many fragmented conversations during the three weeks we were together affirmed the differences in how our minds had developed to perceive the world.

“You are so lucky, you have no discipline, easy school, and freedom,” the Xiaxi girls would say with certainty and envy. “All we get to do is study.”

I felt guilty about my “luck” and the truth in their words. Still, their idealistic views about America and the ease of my life perplexed me. They had quickly dismissed my out-of-school activities and community service as lacking real learning. Yet, soon I realized how their understanding of “smart” contrasts with mine. Being smart is the high ranking a teacher gives them; studying is their only way of getting there. These tight borders command their childhood.

I permeated those borders as we talked about growing up, gender roles, equality, and relationships. No one before me had given them the space to talk about such topics. As a girl born in Xiaxi and living in America, I was the most foreign person these girls had ever met. They had never come in contact with anyone who looked different from them. When I told them about the many friends I have who look different than I do, they were astonished. Being with them gave me deeper appreciation for the diversity that my life in America affords me.

For those I met in Xiaxi, family is blood and ancestry. “You do not know your real parents?” strangers would ask me soon after we met, sympathetic and eager to help me find mine. “When is your birthday? What orphanage were you from?” Their words “real mother” sat heavily in my mind. Even if I’d spoken their dialect fluently, I am not sure I could have explained. I have a real mother, the woman who raised me and loves me. My biological family might not be whom I romanticized them to be, and finding such strangers would not instantly conjure love. Instead, it was in the welcoming care that countless strangers showed me—in placing watermelon slices in both of my hands, pulling a comb through my hair, and attempting to cool me in 110-degree heat—that I found home in Xiaxi, and that was enough.