I am a serious student of Parenting Theory. I collect parenting books the way a gourmet collects cookbooks. And I once presumed I had a fairly complete parenting tool belt.

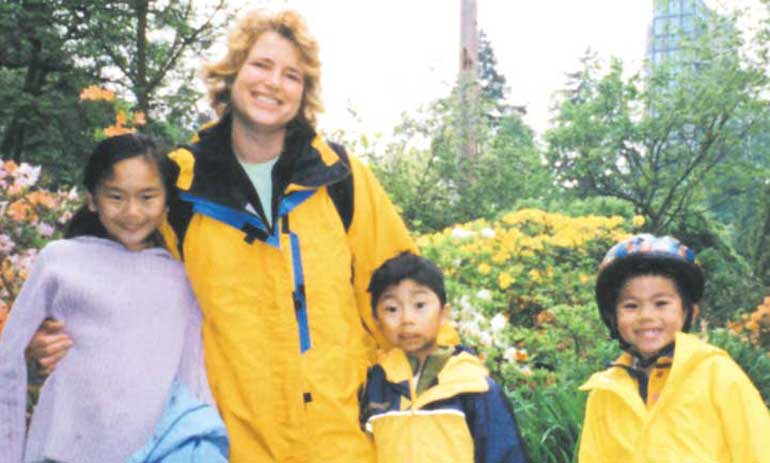

Then came Christopher, who arrived in our home a few months after his third birthday. I was already an effective parent to two children; why wouldn’t I do just as well with a third?

What I didn’t know was that conventional parenting techniques are often ineffective when used on children undergoing transition and trauma. Children who have spent their early years in institutions or in foster care require another approach, one you rarely read about in parenting books. My tool belt, it turns out, was lacking some vital equipment.

A Counterintuitive Approach

When my first child was two, I took a class called STEP (Systematic Training for Effective Parenting). The system involves active listening, establishing which problems a child owns, helping her solve them, and allowing her to experience natural or logical consequences. When my little one felt cold, she learned to wear a coat next time. I helped clarify her ideas, and she was quick to solve her own problems.

But active listening is hard to do with a child who won’t or can’t communicate. In Christopher’s case, there was a language barrier. And even as that dissolved, he was not much of a communicator. The trust and ability to share just weren’t there.

Where some children might say, “I don’t want to go to daycare,” Christopher would simply refuse to come downstairs. Active listening wasn’t an option, but sitting with him and saying “Are you feeling anxious about leaving Mommy?” sometimes worked. It took a while to figure out that he didn’t come downstairs because riding in the car made him feel sick.

Logical consequences are a mainstay of most parenting plans. Yet with Christopher, they didn’t work. He was so used to being uncomfortable — cold, hot, hungry, even sick or hurt — that he did not respond to the kind of discomfort that sends other kids scurrying for jackets.

To make him live with the consequences of, say, forgetting his sweater, was not only ineffective, it was downright mean. I had to help him identify what his body was experiencing. I had to name the cold he felt when the wind blew, then demonstrate how we block it. I had to teach him that he has the right and the ability to be comfortable. How counterintuitive! With my other children, I allowed them to feel discomfort and learn from it. With Christopher, I had to teach him to be comfortable.

Of course, logical consequences go beyond physical comfort. Many of us use isolation — a time out — as a consequence for anti-social behavior. You can’t be nice, so you have to go away. But when an older child is adjusting to a new family, this is exactly what you don’t want to do.

In Christopher’s case, there were plenty of tantrums. But to isolate him, even in a corner near the rest of us, was to reinforce the idea that he was “bad,” unworthy, not a permanent part of the family. It fed his enormous fear that he might in fact lose this home and family at any moment.

What I needed to do was slow down, sit, and hold him, even as he raged, and assure him over and over that I would be here for him to help him through this hard time. Unlike my other children, who were given little or no attention when acting out, Christopher needed more attention at such times.

Those Vital Early Years

I am learning that I don’t need to parent Christopher today in the way I hope to parent him as a teenager. Instead, I must think of him as a younger child, incapable of the responsibility I expected of my other children by the time they turned four.

For now, I must own his problems, because he isn’t ready to own them himself. That doesn’t mean he won’t be some day! But it does mean that I need a bigger parenting tool belt, with different tools for different kids. I have to give Christopher the early childhood he never had.

One of the parenting principles that’s worked for me is to meet the child’s every need for the first two years, then begin showing them how to meet their own needs and how to fit into the world at large. You feed a baby on demand, but you teach a toddler to eat on the family’s meal schedule. Adopting a child of three looked easy: he would be ready to fit in. I now know that there’s no skipping that first year or two of meeting every need.

Yes, it is strange to see a child so large and so seemingly competent asking to be carried or becoming distraught when a request for food is not quickly met. But I have learned there is no point in expecting him to wait for food or other basics. I have also learned that doing this will not “spoil” him. There is plenty of time to help him grow up and learn to fit in. It isn’t the kind of parenting I planned on, and it’s not what I hope to be doing in a few years. But I believe it is the kind of parenting that works with a child who never knew the joy of a nurtured infancy.

I recently read Parenting with Love and Logic, a good source of a few new tools for my belt. Authors Foster Cline and Jim Fay describe several ineffective parenting styles, including that of the “Helicopter Parent” who constantly hovers, ready to swoop down and rescue the child from all difficulties.

It’s easy to see why it wouldn’t be effective to parent my other kids in this way. But then there’s Christopher. He has never had anyone who cared enough to help him remember his jacket and to sit with him when emotion overwhelmed logic. How wonderful to be the helicopter in his life.