A while back, my 15-year-old son Mateo came home and told me this story. He’d been at the gift store at the bottom of our hill to buy a fancy candle for a friend’s birthday. Mateo shops at the gift store a lot—he’s a generous giver of gifts to friends—and the shop owner knows him. But on this day, a different woman stood behind the cash register.

Mateo brought the candle to the counter, opened his wallet, and pulled out a $20. He handed the bill to the woman. The woman promptly held the bill up the light and examined it to make sure it wasn’t counterfeit.

“She wouldn’t have done that to you,” Mateo said.

“Because I’m old?”

“Because you’re white,” Mateo said. “Also, if I were going to use a counterfeit bill, wouldn’t I have paid with a $100?”

“I guess she didn’t notice your Michael Kors wallet,” I said. “Or your Air Force One sneakers.”

“No,” Mateo said. “She just noticed I’m Latino.”

Another day, my 17-year-old daughter Olivia told me this story. Normally, Olivia comes home on the school bus, gets picked up by a carpool, and is driven up the steep hill to our house. But on this day, the carpool driver had a scheduling conflict, so Olivia had to walk home from the bus stop. It was one of those scorching hot afternoons in California, and Olivia stopped at the local market to buy a lemonade before beginning the vertical climb. Her backpack was filled with heavy books, and in a few minutes, Olivia started sweating. She stopped on the sidewalk under the shade of a tree to drink her lemonade.

As she drank, the woman of the house with the shade tree opened her door. She stood in the doorway and watched Olivia drink her lemonade. Olivia got nervous being watched. She wondered if there was a law she didn’t know about. A law against drinking lemonade under a shade tree next to the sidewalk. Olivia put away her lemonade and continued walking up the hill. The woman came out of her house and followed Olivia. She walked behind my daughter for several houses, until the hill got very steep and she turned around.

When Olivia told me about the woman, I asked her, “Why didn’t you tell her you live on this block? That you were going home?”

“What was she going to believe?” my daughter said. “That I live in a house on top of the hill? That my dad’s a doctor? Or was she going to believe I didn’t belong there, that I was wandering around the wrong neighborhood.”

“Didn’t she see you were dressed in school clothes? That you were carrying a backpack?”

“No,” Olivia said. “All she saw was that my skin is brown.”

As my kids become adults and move into the world without me, I can’t protect them the way I could when they were little. I can’t assume they’ll walk into a store or up a hill or anywhere else and be cloaked with the same privilege I was born with. I live with the fear they’ll make a misstep, or what’s perceived as a misstep, and that some innocent action will lead to tragedy. As we’ve seen—as the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Michael Brown, and too many others have seen—this is not an unfounded fear in this country.

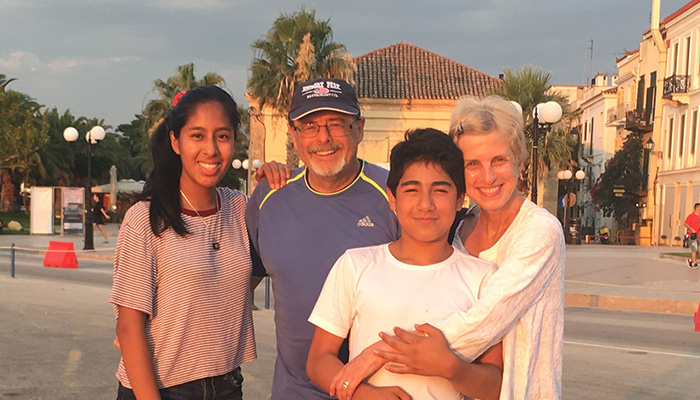

When we decided to adopt from Guatemala, I never projected ahead twenty years. I didn’t anticipate the world my children would face. Of course, I understood racism existed, but it had never touched me directly, the way it does for my children. My parents never had the talks with me that I have, often, with my children: If you’re stopped by the police, keep your hands on the steering wheel and describe your every action when you reach for your driver’s license. Never wear a hoodie with the hood up. Understand that some people will make assumptions that have nothing to do with who you are. Know that you will be held to a higher standard. Be extra cautious even when your friends don’t have to be.

There’s so much I can’t control, but also a few things I can. I can acknowledge my own subconscious biases and strive to eradicate them. I can vote. I can protest. I can continue to have these conversations with my children, embrace their birth culture, and include people of color in our direct circle. I can write about my family’s experiences.